Our Origin Story

The Early Years

Steve Crocker spent his teenage years in the late 1950s and early 1960s alternating between Evanston Township High School near Chicago and Van Nuys High School in Los Angeles. As a “math geek who had taken refuge and enjoyment as a kid digging into math,” he was drawn to kindred spirits: In Evanston, he and Bob Axelrod competed in math contests and taught themselves programming. In Los Angeles, he started a math club with Vint Cerf.

The boys’ shared love of math led them to a pivotal interest: computers.

Steve had his eureka moment when he was 15 years old, when he audited in an Introduction to Computing extension class at Northwestern University.

“I remember very clearly the feeling I had when I realized that with a relatively small set of instructions, you could get an arbitrary amount of work done, because you can get it to repeat over and over, and keep doing the loops and conditionals and so forth,” Steve says. “That idea took hold of me.”

Bob recalls the day Steve asked if he wanted to learn to program. He said yes, and the two were soon programming with punch cards on Northwestern’s single computer, which users could play with for 15 minutes at a time.

“I was fascinated with computers, because, like in math, there’s confidence in the validity of the outcome,” Bob says. “There might be a bug, just like there might be a mistake in a proof. But when you got it right, it wasn’t a matter of opinion, and it was under your control.”

When Steve returned to LA in 1960, he “burrowed [his] way into what constituted the computing establishment” at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Vint soon joined him, and they learned to use the Bendix G-15, which was programmed with small steps on paper tape.

“For me, when you’re writing a program, you create this little world, and you’re in complete control over it — it does whatever you tell it to do,” Vint says. “I found that ultimately beguiling.”

On one memorable Saturday in 1961, Steve and Vint drove to UCLA, but discovered the building was locked, even though Steve had permission to use the computer. Steve figured the day was a loss, but Vint spotted an open second-floor window.

“While I’m pondering, he’s clambering up on my shoulders, climbing in,” Steve remembers.

They taped the door open and spent the day programming.

A decades-long friendship forms the foundation and shapes the philosophy of the Ice Preservation Institute.

Bendix G-15, an early computer. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum

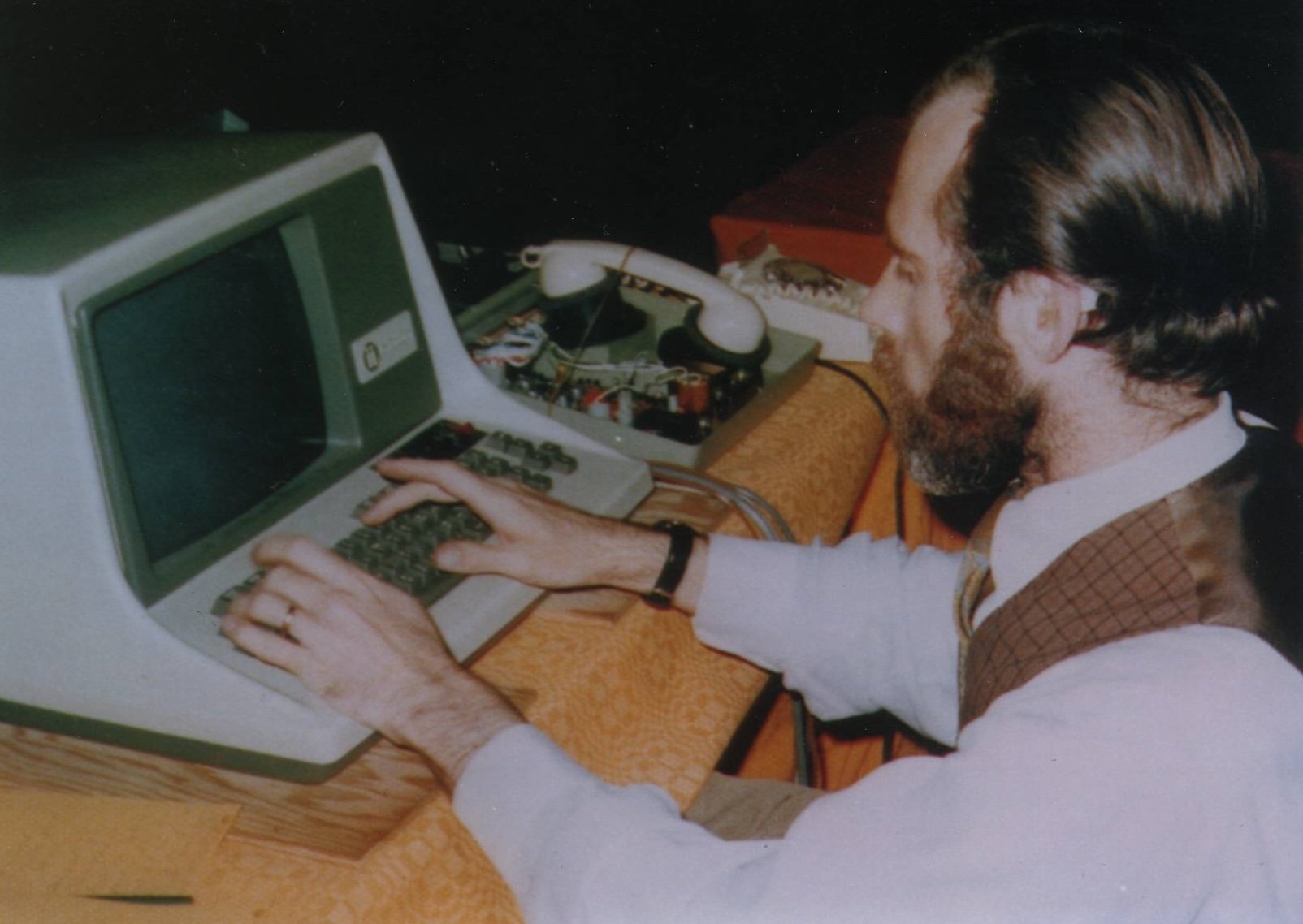

Vinton Cerf demonstrating ARPANET in South Africa. Courtesy of the Computer History Museum

From Computers to Climate Change

After high school, the three went on to study math as undergraduates: Steve at UCLA, Vint at Stanford and Bob at the University of Chicago.

Their fascination with understanding the way computers and the world work led to their notable careers. Steve was part of the UCLA team that developed protocols for the pioneering ARPANET project, and he became a global leader in information sharing and Internet security. Vint, who was also part of ARPANET and is known as a “father of the Internet,” is a longtime vice president at Google. (Steve and Vint also worked at different times for DARPA, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.) Bob was eager to work on real-life problems of international security, so he went on to earn a Ph.D. in political science. He became best known for his work on the evolution of cooperation.

Steve stayed in contact with his oldest friends for years to come. He and Bob scheduled regular chats about a multitude of topics, and in August 2020, they invited Vint to join them.

That summer, they began weekly Zoom meetings to discuss urgent public policy issues.

“We kicked off the Saturday morning set of calls first with open-ended discussion of what big things we could think about where we might be able to apply some novel ideas,” Steve says. “By this time, each of us had pretty full careers, a lot of contacts, a lot of context and a lot of different ideas floating around.

They settled on climate change as their focus. None of them have technical expertise in the field, but they saw it as an important place to lend their insight and influence.

Vint jokes that those early talks should have been called “the Saturday Hubris Discussion.” They learned about many climate problems and technologies, but couldn’t find a place to focus.

In October 2021, they brought in Baruch Fischhoff — a Carnegie Mellon professor and a friend of Bob’s through the World Federation of Scientists — to share his expertise in communication and his reputation as a “procurer of experts.”

The group’s turning point came in 2023, when Bob’s daughter, Vera, met Alex Luebke while scuba diving.

Alex had done work at Google’s “moonshot factory,” developing technology to mitigate climate change. But he realized that mitigation wasn’t enough to solve the problem — and what was needed to protect our civilization was climate interventions “to hold the planet together just long enough that we can fix all the other things.”

Vera knew her father would be fascinated with Alex’s ideas. In March 2023, Alex joined his first Saturday call. Soon after, their focus turned to the potential for anchoring Thwaites Glacier, and the Ice Preservation Institute was born.

Vint Cerf at UCLA working with SIGMA 7 computer and ARPANET. Courtesy of Computer History Museum

A Philosophy of Openness and Collaboration

Alex admired how Steve, Vint and Bob’s early computing experiences and pioneering careers shaped their mindsets.

“There’s a very specific philosophy that kind of comes from this moonshot era, right from the ’60s, that says, ‘Look, we can take on really audacious goals, but there is a method to doing that,’” Alex says.

Vint and Steve’s time with ARPANET and DARPA showed them the power of a large cohort of people who want to tackle hard problems, which has motivated them to invite experts in many fields to join their discussions.

Their careers also showed them the value of welcoming surprises and inviting participation from unplanned areas — an approach that has been central to the Ice Preservation Institute’s multidisciplinary workshops.

Bob, who has spent his career studying cooperation, notes that the collaborative and non-competitive environment that helped create the Internet is also important to the Ice Preservation Institute.

Collaboration doesn’t always mean agreement. They’ve intentionally included people who might argue against their ideas.

Their core friendship provides a model for constructive disagreement.

“Trust and respect are really important elements in the way this has worked,” Vint says. “Even when we have had discussions, debates, disagreements and so on, we knew that nobody was trying to shoot at somebody else. The whole point was everybody was trying to get to a solution that worked. The motivations were all positive, and I think that’s contributed a lot to our progress so far.”

The Ice Preservation Institute is still in its early stages. The task ahead is enormous and complex — more than a moonshot, because it’s global. But the team knows it’s worthwhile.

“It’s our mindset that we have an obligation to use the resources we have, and the skills and gifts we have, in order to save something very, very special,” Alex says.

The sense of discovery, collaboration and possibility that began with three teenage math geeks 65 years ago continues to fuel them as they forge ahead.

“There is something about the spirit of this group, whose roots are in the triumvirate friendship, that has carried through,” Baruch says. “And I think that has got people willing to give us a chance.”

Workshop attendees at the groups first in-person workshop at Stanford University; December 2023.

Ice Preservation’s second workshop in New York City; September 2024.